From Greece to Rome: Building a Roman Perseus

Gregory Crane

Tufts University

Four years ago, after almost a decade working on Greek Perseus, we turned our attention to the Roman world. We had published the first Perseus CD ROMs in 1992 and, already in 1996, Greek Perseus had begun to attract a great deal of use on the World Wide Web. Students and teachers at various levels had demonstrated their interest, both by direct comments and by actual use of published materials, in having access to as many primary sources, both textual and visual, and supplementary materials (lexica, cataloguing data, essays etc.) as possible. The Perseus Web site had, in fact, emerged as a "wholesale" clearinghouse for integrated primary materials. We found individuals building a wide variety of course materials on top of the foundation laid by Perseus, with courses ranging from middle school to graduate seminars all directing their students to use Perseus in different ways. Support from the National Endowment for the Humanities helped us and two other projets get started. The VRoma Project (www.vroma.org) set out to train US high school teachers. Professor Joseph Farrell's Vergil Project focused its energies on developing (in collaboration with secondary teachers) an electronic "edition" for Vergil. Subsequent support from the NEH will allow us to run seminars for teachers in 2000 and 2001, but in our first years of work we set out to complement the efforts of our sibling projects: participants in VRoma have been able link into sources that we have placed on-line, while the Vergil Project was able to base part of its work on data that we created. Our first priority was to establish a reasonably substantial, well-integrated and open-ended "digital library" for the study of Roman culture. We knew that we would not be able to create a comprehensive collection given the resources and time at our disposal but we felt that we could create something of immediate use that would grow over time. This paper describes where we stand now and where we hope to go.

Designing for a Digital Environment: Possibilities and Challenges

A great deal of work remains to be done on Roman Perseus but the outlines of a coherent digital library are now beginning to emerge. Language stands at the heart of any database of cultural materials – culture and language are so inextricably interwoven that any system that sets out to represent a distinct culture must help its users work with its particular language (or languages). But if language is the essential starting point, we also need multimedia materials to document the physical context as well. Such visual materials can include not only still-images but sound, video, and emerging tools for virtual tours or 3D representations of objects. Finally, a system faithful to the needs of the domain must integrate the various elements together. A simple web site where users can search for images and texts constitutes only a first step in this direction.

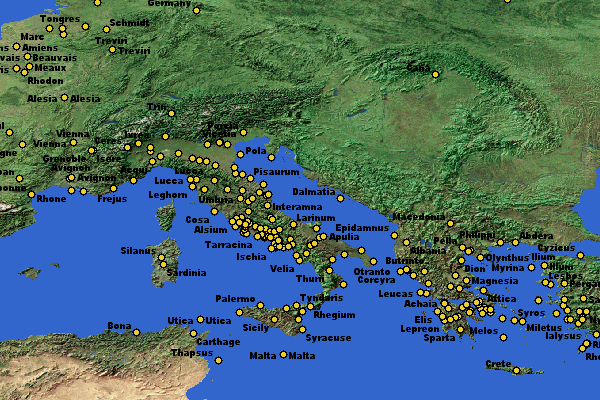

We are studying the interaction between content and system because each affects the other. In a mature digital library, "books" interact with one another. A electronic historical text (e.g., Cicero's Letters or Caesar's Gallic Wars) can, for example, be combined with an electronic atlas to generate maps of places mentioned in a given text. Figure 1 shows a map automatically generated from within the Perseus Digital Library and plotting places mentioned in Cicero's Letters.

Figure 1: Places mentioned in Cicero's Letters.

The above map reflects only an initial effort in a long-range project but the potential of such "visualization techniques" is considerable. Users can zoom in until the names for all sites are visible. They should be able to (but cannot yet) click on sites and call up a list of places in Cicero or Caesar where they appear. It would also be easy, for example, to create an animated version of the above map, plotting in sequence the various places from which Cicero writes or the locations mentioned by Caesar in a given book of the Gallic Wars. Such an animated map would allow the viewer to grasp the shifting geographical focus of a document filled with unfamiliar place names.

The benefits of such interactive tools are not, however, always an automatic by-product of electronic publication. If we write for print, we may find that we have missed crucial opportunities that, with relatively little extra effort, we could have exploited. Some of Cicero's most interesting letters describe how Brutus' agents violently extorted money from the people of Salamis in Cyprus (e.g., Cic. Att. 6.1). A digital library system has no certain way to determine whether the Salamis in question is in fact in Cyprus or the much more widely mentioned Salamis near Athens. A clever system can probably use the general context to guess the right Salamis most of the time, but such automated inferences are never perfect. A translator or editor going through a text word by word could, however, resolve such ambiguities without adding appreciably to their task – the labor of editing or translating a text far outweighs the extra labor involved in clarifying such points. Thus with little if any substantial added effort, one could create a text that would work well with an on-line atlas.

Since we as classicists prepare documents for use over a long period of time, it should make little difference to us whether the electronic atlas is available now or ten years from now. If we assume that an on-line atlas is likely to become available at some point in the foreseeable future, then we should think seriously about preparing works accordingly.

There are two problems. First, in some cases we can see how we might change our practice as authors and editors. Every serious electronic edition should, for example, disambiguate places (which Salamis?) and people (which Brutus?). This is simply the logical extension to the indices of places and names with which we are all familiar. But creating a system that allows practicing editors to encode such information is not easy. We need to assemble "authority lists" (widely recognized ways of distinguishing various people and places) and standard word processors are not set up to facilitate such tagging. We also need to develop our Latin and Greek tools – the "authority lists" that we now have are in English and we currently generate maps from English translations rather than from Latin or Greek source texts. We may thus know what we want to do but then lack the tools needed to accomplish the job.

Second, there are surely other things that radically enhance the value of an electronic edition and that editors could easily do as a part of their work, but we do not yet know what these new features will be. Readers can do different things with electronic texts and these new functions will in turn influence the way in which we structure those texts, but we cannot anticipate what these features will be. The only way to make progress is to develop new systems and to see where they take us. Developing a Roman Perseus is thus important not only because of what it lets us do now but also because it provides concrete examples of how we, in creating documents about the ancient world, could take fuller advantage of evolving digital environments.

Those of us who work on particular projects may have their own opinions as to what is and is not valuable. In the end, however, the best designs emerge from communities. A Project such as Perseus can suggest possibilities and make features available, but the response of students and teachers will ultimately shape the "best practices" for electronic resources. We thus need not only to create new ways of working with classical materials but to make these new methods available to the widest possible audience.

Roman Perseus 2000

All cultural digital libraries are (or should be) open-ended and there is no limit to the materials that could be assembled to document the Roman world. In a relatively short development period and with limited resources, one needs to assemble a practical collection of contents within a workable system. We chose as a fundamental principle to concentrate on materials that were diverse in form and that we could make freely available on the Web. The following briefly describes the collection that we assembled. Although the textual and visual components developed in parallel, the order of individual jobs is significant in that it reflects the stages in which we chose to build the collection and thus reflects the priorities with which we worked.

Textual Coverage

- Latin Morphology : Since we consider language to be the core of any cultural digital library, we began by developing tools for managing Latin. Since Latin is a highly inflected language, we needed to be able to map inflected forms (e.g. fecerat) to their dictionary entries (e.g., facio). We had a working model for Greek that allowed users to go from inflected form to dictionary entry (e.g, click on fecerat and lookup facio), ask for a dictionary entry and retrieve inflected forms (e.g., ask for facio and retrieve fecerat), and display statistics on usage (e.g., let a user see that facio is fifteen times more common in Plautus than in Horace). We were able to adapt the morphological analyzer developed for Greek to Latin. Our experience in this process confirmed our assumption that Latin morphology was fundamentally simpler than Greek. Most of our effort in this adaptation went into creating a Latin mode for the analyzer that turned off features to deal with phenomena such as accents, dialects, preverbs and other aspects that render classical Greek computationally (as well as intellectually) complex.

- An On -line Latin Lexicon – Entering Lewis and Short: A morphological analyzer can identify stems and endings and can recognize legal Latin forms (e.g., it can recognize that the stem fec- and ending -erat can, in fact, be combined to make a legal Latin word), but it requires a database of stems and endings and the larger the database, the more powerful the system. Our second major task in building Roman Perseus was to enter Lewis and Short, not only so that readers would be able to call up its definitions but also and more immediately so that we could "mine" the lexicon for morphological information. We wrote programs that would recognize "inventor, oris, m.," for example, as a masculine third declension noun, breaking the form up for computational purposes into a stem (invent-) and ending (-or, -oris). In this way, we were able to develop a database of 44,701 nominal and 16,935. verbal stems.

- Latin Source Texts and English Translations : Two principles guide our selection of texts. First, we always try to include English translations as well as Latin source texts. Some students may use the translation as "trot" and thus fail to develop their language skills, but many of our most conscientious users are serious researchers – whether students or tenured faculty from outside of classics – work in isolation and need the English translations to verify their tanslations. Second, we try to provide "depth" of coverage. Rather than providing an overall anthology of Latin, we set out to provide some depth for the first century B.C.

- Commentaries: At present, we have entered and formatted John Connigton's Aeneid, Allen and Greenough's Select Orations of Cicero and Caesar's Gallic War, E. H. Donklin on Cicero's Pro Roscio, Frank Frost Abbott's Selected Letters of Cicero, Merrill's Catullus. Paul Shorey's Horace: Odes and Epodes. All of the preceding commentaries are either now available or in the final stages of preparation. Our goal was both to provide useful information and to give examples of on-line annotation. By putting older commentaries on-line, we developed a framework in which newly created comments could be built.

- Charlton Lewis, Elementary Latin Dictionary : A private donation allowed us to enter a smaller lexicon so that students would have an alternative to Lewis and Short. At present, this student lexicon is being prepared for publication on the web.

The decision to begin with Lewis and Short had serious implications for the rest of our work. Lewis and Short is famous for its small print and poor legibility. It is also quite large – roughly 4.5 million words and 30 million characters in length. And entering a lexicon is an "all-or-nothing" job. We had to commit almost all of our budget for professional data entry to Lewis and Short. All of the Latin source texts and English translations needed to be scanned with Optical Character Recognition (OCR) software. This proved immensely laborious and the results were not always satisfactory. Ultimately, we were able to acquire very powerful (and expensive) OCR software that produced much better results but only after we had entered the bulk of the Roman Perseus texts.

At present, we have 1.3 million words of Latin, representing works from nine widely read authors: we have the major extant works of Plautus, Suetonius, Vergil. and Catullus; besides these we have Caesar's Gallic Wars, Horace's Odes, Cicero's Orations and Letters, the first ten books of Livy and Ovid's Metamorphoses. We have entered and are preparing for release the lives of Plutarch not already in Perseus. There are tentative plans for adding the Greek source texts, as well as important sources such as Appian and Dio Cassius. There are still major gaps – we do not, for example, have Sallust yet – but the corpus that we have assembled represents a starting point.

Allen and Greenough Latin Grammar: Our online version of Smyth's Greek Grammar had become very popular. We therefore decided to enter Allen and Greenough's Latin Grammar. Given the complex formatting of A&G, we needed to send this out for professional data entry and were fortunate to receive local support for that task.

Art and Archaeology

- Roman Art in the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston : In parallel to our textual development, we collected 5,700 original images of 781 coins and 327 other objects, including portrait heads, sarcophagi, full-size statues, bronze statuettes, funerary reliefs, mosaics, pottery, glass, jewelry, and architectural fragments. Amy Smith, the Perseus curator for ancient art and archaeology, and Maria Daniels worked closely with the MFA curatorial staff to assemble up-to-date documentation for these materials. The first set of MFA materials – the coins – went on-line as part of Perseus in the spring of 2000. The rest are being prepared for release.

- Site Photography : We set out to collect a core of images documenting Rome and Italy while beginning a series that began to represent the Roman provinces. Given the time frame and resources at our disposal, we knew that we could not do a thorough survey but we felt that we could create an initial core that could, like the textual materials, grow over time. The following table describes the visual materials collected as part of Roman Perseus:

|

Images |

Location |

Photographer |

|---|---|---|

|

2963 |

Rome |

Maria Daniels |

|

182 |

Italy |

Jacqui Carlon |

|

143 |

Italy |

Amy Smith |

|

635 |

Italy |

Jodi Magness |

|

473 |

Spain/Portugal |

Michael Ramage |

|

375 |

Croatia |

Maria Daniels |

|

232 |

Jordan |

Amy Smith |

|

149 |

Spain |

Al Kaiser |

|

1274 |

Gaul |

Maria Daniels |

|

2545 |

Turkey |

Maria Daniels |

|

55 |

Greece |

Amy Smith |

- General Site documentation : To provide information about Roman (and Greek) sites, we entered the Princeton Encyclopedia of Classical Sites. PECS contains 1.2 million words covering 5,000 entries. In addition, we are preparing Platner and Ashby's Topographical Dictionary of Rome, with coverage of 2,000 topics specific to Rome and its environs.

- Intensive Documentation of Ostia : As with museum photography, we knew that we could not collect extensive site photography on the scale that had been possible for Greek Perseus. In our earlier work, we had been able to create hundreds of site plans, in some cases linking several phase plans together so that users could view the development of the site sequentially over time. Such coverage was not generally feasible for the first phase of Roman Perseus, but we decided to choose one site that was complex in form and central in importance but that would be manageable. Ultimately, we chose the Roman port city of Ostia, a well-studied and excavated site. Smaller than Pompeii and Herculaneum, Ostia is nevertheless a very large and complex site and provides a crucial window onto Roman social and economic history. At present we are assembling 10,000 images of Ostia into a single virtual tour of the city.

- Geographic Information : The Perseus Atlas already contains more than 3,000 places from the Greek world. Most of these points were derived from sources with relatively coarse resolution (e.g., c. 1 km). We are preparing to supplement these points with data from other general sources (such as the Getty Thesaurus of Geographic Names) so that we can better represent the western Mediterranean. In addition, handheld GPS units can now provide coordinates that are accurate to within 10 m. We have begun collecting and soliciting these much more accurate coordinates as well. Ultimately, we hope to see an open database of geographic coordinates for classical sites to which many would contribute and which various projects could exploit.

Overall Integration: Who, What and Where? Harper's Classical Encyclopedia

The "encyclopedia" in Greek Perseus consisted mainly of very brief glosses. We knew that such general information was heavily used and we wanted to expand on what we had. The new OCD3 would be an ideal on-line resource but we wanted at this stage of development to focus on resources that could be made freely available to the widest possible audiene. We therefore decided to enter Harper's Classical Dictionary to provide basic information for people, places and things in the ancient world. Its 11,000 entries cover a wide range of topics and its 1.7 million words provide a great deal more information than we could assemble in a short period of time. Once Harper's is available on-line, we would be in a good position to update old or add new entries.

Future Work

A great deal of fundamental work remains to be done. We need to refine and complete some of the work described above. We need a new interface for the Perseus Web site that makes it easier to locate Roman materials as they come on-line. And we have much more to do – there are many texts, commentaries and similar existing print resources to convert into electronic form. Such work always requires time and labor and often funding as well (some documents, for example, simply do not lend themselves to OCR and must be sent out for professional (and costly) data entry. Raising money to expand our holdings is an on-going challenge.

At the same time, individuals can do much to contribute not only to Perseus but to the on-line resources that all of us in classics can share. We have worked closely with the Stoa Publishing Consortium (www.stoa.org), which is helping classicists develop a variety of new resources, many of which can be added to Perseus itself or to which Perseus can establish links. Contributions range from new commentaries and editions (e.g., Laura Gibbs' work on Suetonius) to students collecting digital images of sites or GPS data as part of class trips.

None of us can really anticipate the effects that new technology will have upon the field of classics, but both our students and we can look forward to challenges as well as opportunities. Our fundamental job remains the same – we need to learn as much about the ancient world as we can and then transmit that to coming generations – but the age in which we live has given us exciting new tools with which to pursue our job. Technology by itself is never the answer, but it will surely be part of any long-term strategy that promotes the study of classics. Individual projects, however ambitious or modest, all seek to contribute to this larger goal.